Photographer Spotlight: Steven Phipps

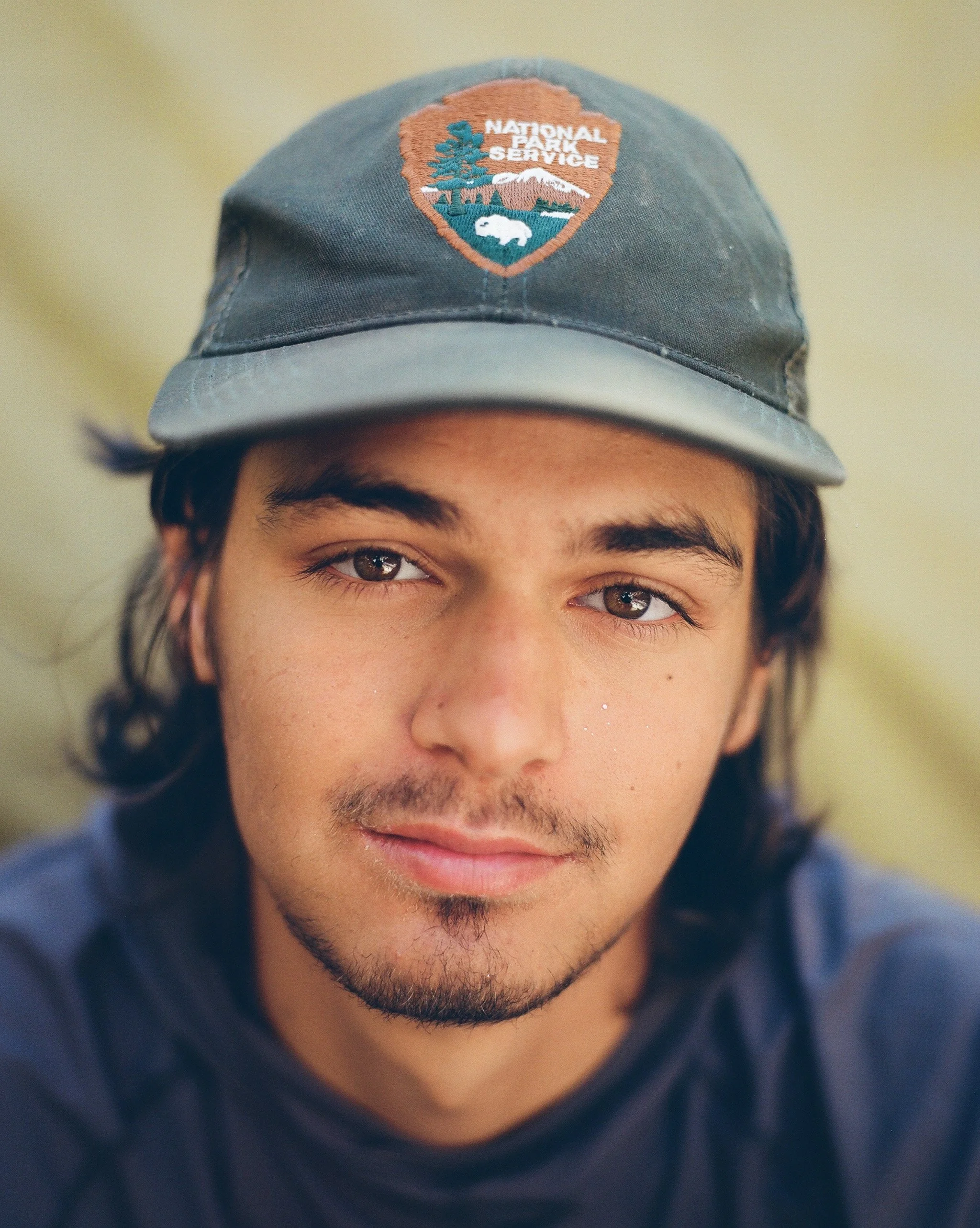

Steven Phipps. Photograph by the author.

I met Steven Phipps on a breezy ridgeline at about 10,000 ft in Grand Teton National Park, where he and his crew were repairing rock walls on the Static Peak trail. Steven told me he was also a photographer, and we immediately hit it off, although I got the sense that Steven could hit it off with just about anyone—his energy, enthusiasm, and spray of blond hair giving him a youthful buoyancy that typically gets weathered out of older traildogs. But despite being the youngest and least experienced on the crew (he was on an AmeriCorps ACE program called the NPS Academy), it was clear that he caught the spark for trails, and that he, like many trail workers, saw a deeper meaning in the craft and the people.

As I got to know him over the next couple of days on Static Peak, I was impressed by his ability to find opportunity in struggle and his eagerness to learn from it. Perhaps because he even spelled his name wrong for most of his life—he thought he was “Stephen” until high school, when his family realized that it was actually “Steven” on the birth certificate. Instead of being embarrassed by this clerical error, he told me, “I get really excited when people ask if it’s with a “ph” or a “v”. I’m like, boy do I have a story for ya.”

As he explained in our interview, his dive into photography would likely never have happened if he hadn’t gotten sick with COVID-19. He was happy to admit that he’s constantly making mistakes and learning, especially in the finicky realm of film photography. His crew made plenty of friendly jibes that he, a kid from a tiny town in rural Texas, was going to get himself killed in the mountains, nicknaming him “Statistic.” He embraced the nickname wholeheartedly.

Steven’s ability to take it all in stride is probably why his photos are so damn good. If mistakes are tuition in the school of life, he paid for his education quickly. That, combined with the gumption to hike an enormous film camera into the backcountry. The result is a gorgeous portfolio of images that I’m sure we’ll be seeing on a gallery wall someday.

“Jaden Singh at Garnet Platforms, Grand Teton National Park, Jackson, Wyoming (2024).

One-of-a-kind guy. Go check out my post about him to learn more. No bad memories.”

Photo by Steven Phipps

“The background of this shot is actually all smoke. The Fish Creek Fire was tearing through the Gros Ventre range and had created this blanket of smoke in the valley. It was so thick we all woke up with sore throats—luckily, we got to climb to higher elevation for our project.”

Photo by Steven Phipps

Joe Gibson: What first drew you to photography as a medium of art?

Steven Phipps: It started out as just something to do during covid. My mom had this old camera she let me use and I would walk around the woods taking really bad photos of my dogs and some leaves. Then once covid kind of calmed down and I went back to college, I joined the school newspaper as a photographer. A few weeks into it, I found myself on a stage with this rock band and there’s this crowd of 200 people, and the band is getting me to lay on the ground under their guitar player to get some cool shots. There was so much energy involved, I was really having a good time. The venue told me off after for being on center stage with the band, but it was my first time doing concert photos so I had zero clue. The band really liked me and was telling me where to lay and what shots to get.

That’s probably the moment that made me really start to like photography, but I don’t think I started viewing it as art until I became friends with this guy named Addison. Funny enough, it was covid-related again. He was one of my roommate’s buddies and we were all hanging out one night, and the next morning I woke up feeling sick and tested positive for covid. He didn’t want to go back home and contaminate his roommates so we told him to just crash on our couch. Turns out he was an incredible painter and we started talking about art. I don’t remember what we discussed, but I remember feeling really moved by the guy. We’d sit there in the living room and he’d paint and I would edit photos and somewhere along the line I started to think about photos differently. I became really obsessed with storytelling and sharing people who I thought were cool. This was the first time I’d ever felt such passion for anything in my life so I just took it and ran. Eventually I ended up checking out a copy of “In The American West” by Richard Avedon from the library while trying to plan a shoot one day and everything just exploded from there. It was this whole new side of photography that I had never seen before and I wanted to be a part of it.

“This was one of those shots I could see clearly in my head before even picking up the camera — but actually making it happen was another story. We hauled a table and mattress out into a field on a 105-degree day, set it up right beneath a low-hanging branch, and started building the scene.

To get the shot, I climbed up the tree, wrapped my legs around the branch, and leaned out with one hand while shooting with the other. Just as I was about to get the photo, my legs started getting lit up by fire ants — but I hung on and kept shooting. One of the more uncomfortable setups I’ve pulled off, but it was worth it.”

Photo by Steven Phipps

JG: What gets you excited about picking up your camera and shooting photos?

SP: I really love everything about taking photos and documentation. Taking a photo of a friend on top of a mountain after we summit or seeing a cool building or scene while walking down the street with my camera in hand. It’s like creating this way to teleport back there. But what really excites me about picking up my camera is when I meet someone that I really want to photograph. Sometimes I’ll meet someone on the street, online, in a gas station, on a trail, at work, through a friend, at some local business or something like that. And every receptor in my brain is screaming to photograph them. Sometimes I’ve lucked out and happened to have my camera on me, others they’ve been kind enough to come meet me at my studio or they’ve let me into their homes and then other times things just didn't work out for whatever reason. Half the time, the photos don’t even come out good, but that matters less than the initial meeting. It’s really cool to get to share that intimate time with someone. Photography has provided me with some really unique experiences that I wouldn't get anywhere else.

Johnny Springer, trail crew, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (2024).

Photo by Steven Phipps

JG: You prefer shooting analog. What is it about film that you prefer over digital?

SP: One part is just the simplicity of it. I can really struggle with over-thinking or second guessing myself, and when you combine that with a digital camera you get this double-edged sword of instantaneous self-critique. Which can be super helpful to fix mistakes. But for me, I’ll start to unnecessarily obsess with getting a hand positioned just right, or slightly changing the subject’s angle. Just really minute changes that go almost unnoticeable to everyone else. But when you start trying to correct these—especially in portraiture— it can be tough on the subject. You can lose the soul of the photo and you wind up with 200 images that are nearly identical and that just blows to go through. I never want something to look forced and with film I personally have an easier time finding the decisive moment to push the shutter.

That’s not to say I don’t make mess up some things that would be easily avoidable with digital. Like you should see the amount of times I wanna shoot myself in the foot after development because my subjects blinking in every shot. But that’s just part of the process. The good, the bad and the ugly.

Second is just having a physical aspect to my art. I love having something to touch. Loading the film, advancing it, flipping the back on my Mamiya RZ67 to rotate between horizontal and vertical. The sound of the shutter being released. Looking through my negatives. It just feels like something real in an age where everything is online.

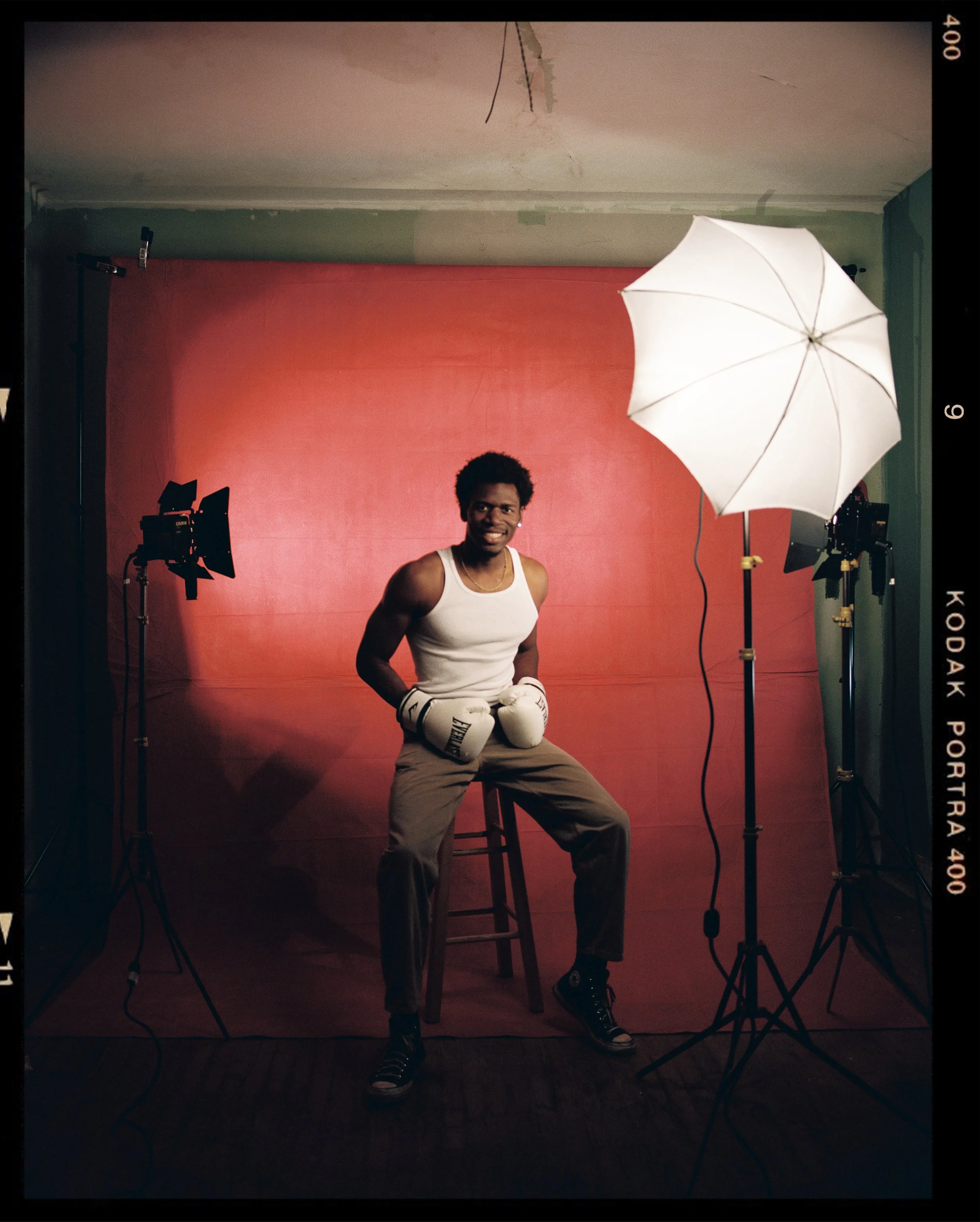

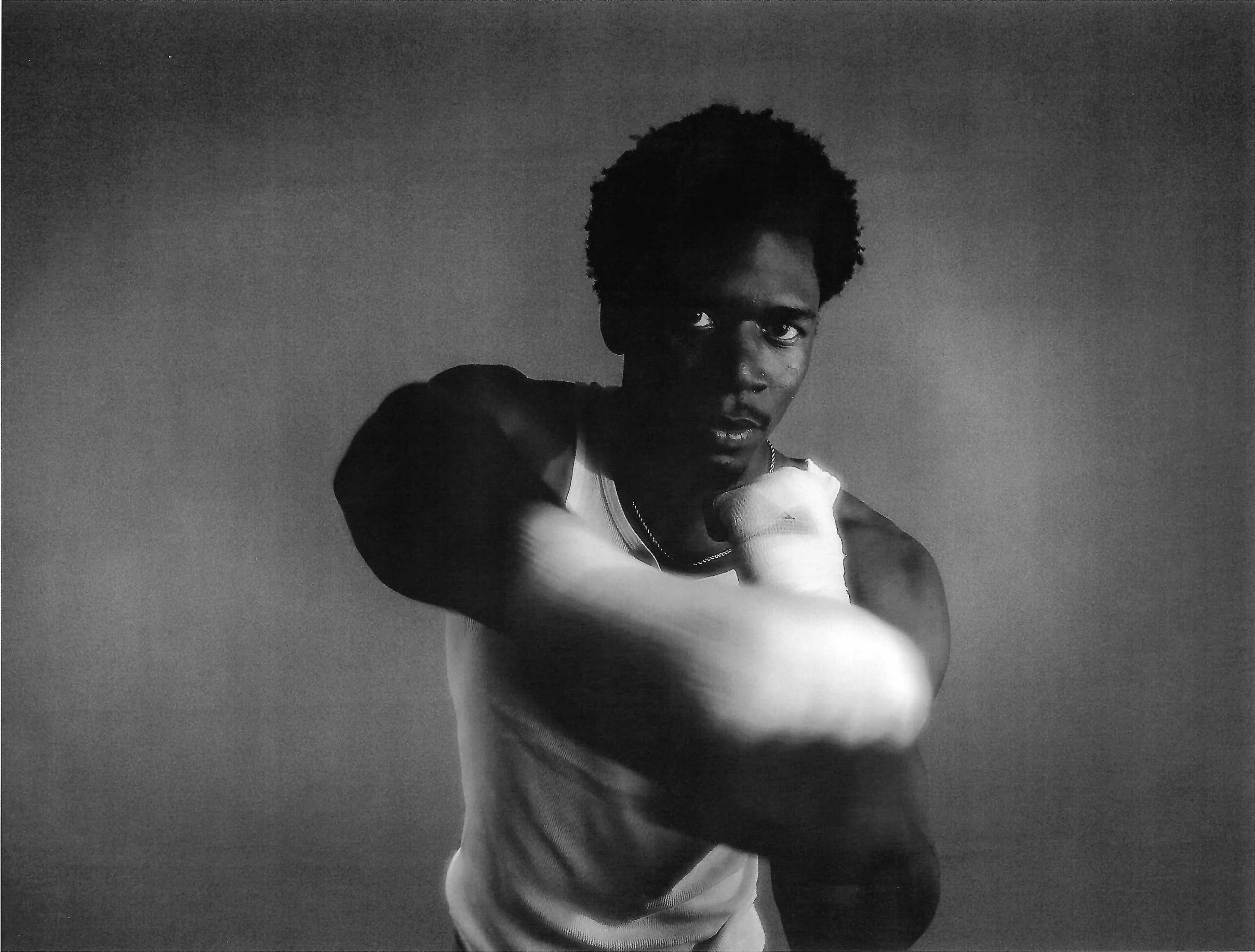

“This was one of my favorite shoots from start to finish. I spent three nights painting the backdrop from sunset to sunrise, which was a great time in itself. The concept — a boxing-inspired shoot — had been bouncing around in my head for months, so finally bringing it to life felt incredibly rewarding.

On top of that, I got to hang out in the studio with some good friends, just goofing arond and making images for hours. There were some kinks along the way — like running out of paint, waiting for things to dry in freezing temps, and dealing with camera issues — but honestly, it still felt like one of those rare moments where you know things are just gonna work out.”

Photo by Steven Phipps

JG: What are some of the challenges of shooting film photos in the backcountry?

SP: My main camera is a Mamiya RZ67 which weighs something like 10 pounds and, with its lens attached, sits around 12 inches long. So lugging this guy around in my pack takes up alot of space and adds some decent weight for big mileage days. With it being so large, I’m always a little afraid of something breaking while it’s swinging around in my pack. It’s a medium format camera, which means each roll of film only has 10 shots, so it can be a little tough to bring and safely store enough film. Also, my last crew did mainly masonry and that rock dust gets EVERYWHERE. Which can funk up my lenses and film real quick. But all the stuff that makes it hard just makes it more authentic. Who doesn’t love a good story with a bit of struggle?

Film and the backcountry just go hand in hand. Everyone’s kinda tuning out of technology while we’re there. Just very little screen time. So the first hitch, I actually brought up my digital camera but it never made it out of my tent. I just didn't like looking at the screen, I wanted it to be more authentic to what we were doing and how we were living.

“Justin Leap, a crew leader at Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (2024).

This guy’s been around the block—he’s a real wealth of knowledge when it comes to all things trail-related. A real trail dog.”

Photo by Steven Phipps

JG: You shot a bunch of portraits of your colleagues on the Grand Teton Trail Crew. What was that like? What are some things you learned?

SP: It was cool and also a little nerve racking. I really wanted to build a relationship with my crew before asking to put this big camera in their faces. Looking back on it, I’m glad I approached it how I did. Once I felt like there was a good sense of comfort and I began asking people for portraits, everyone was super down for it, even those who were initially more timid. When we’d do the portraits, we’d walk away from everybody else for 10-20 minutes and it usually resulted in getting into some deeper, more personal conversations or just sharing some good laughs. I really like portrait photography because it’s such a good path for connection as well as documentation.

It taught me to always take at least two photos because even when you don’t think someone blinked, they usually blink. I got some of my photos back after development and my heart just initially dropped because I had these beautiful portraits 10 miles deep in the backcountry, and you can see the hard work etched into the photos of these people but their eyes were closed. I was devastated at first because I only had one portrait and no chance to ever recreate that moment, but honestly the shots with closed eyes have started becoming some of my favorites. They are just a little different.

“Kennedy Kane at Static Peak hitch camp in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (2024).

Kennedy Kane - you just can't hear that name and not think of a superhero. Well she is.”

Photo by Steven Phipps

JG: Who are some of the photographers who have inspired you the most?

SP: For portraits it’d be Richard Avedon, Arnold Newman and Diana Arbus. The main being Richard Avedon. His book In the American West is what inspired me to do my trail crew portraits the way I did. The stark contrast between background and subject is so fascinating to me, I could flip through his photos all day. It allows so much attention to be drawn to features that would typically slip by unnoticed. They feel so personal and true to life. Instead of bringing a white backdrop, I relied on the nature of my surroundings. The brown bark of a tree, a clear blue sky, gray stone, white wall tent, green leaves. Just whatever was around me at the time that had the right lighting and would give me a solid color background.

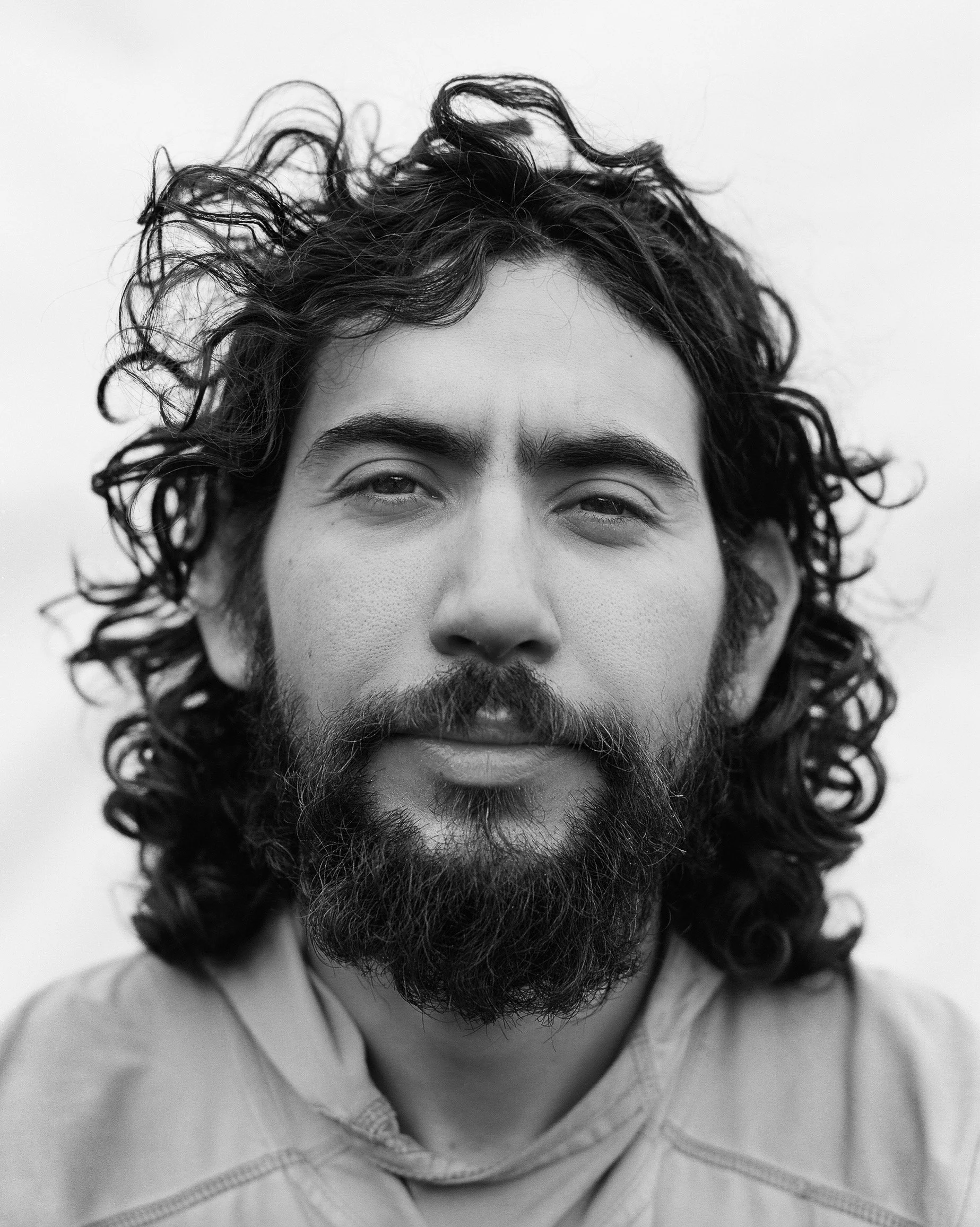

“Bernabe (Bernie) Plascencia – trail crew, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (2024).

A man of his own creation. One of the hardest workers with the gentlest soul I've ever met. One day, we were working on some high alpine switchbacks when the superintendent showed up with a box of fresh-made cookies. We all ran over, snacking and chatting. Not Bernie—he just kept swinging. Good man.”

Photo by Steven Phipps

JG: Can you select one of your favorite photographs and tell me the story behind it?

SP: I was back in Austin, TX, doing a shoot for this local fashion and art magazine called Glaze. When you’re working with them, you get put on a team of 5-6 people that consists of a photographer, stylist, hair and makeup artist, and then 2-3 models. We’d been working like crazy for a month to bring this shoot together. Sourcing all the clothes, coordinating schedules, I was scouting locations and fleshing out the shoot concept and then before long it was all set and ready. So I show up to the location and we start to get things ready for the first shot and I’m grabbing my camera bag and realize that I only have one roll of 120 film. Somehow in all my prep I’d forgotten to buy film.

So I start kinda panicking because we’ve been planning this for the past month, we’re an hour away from the closest shop, and I’ve only got ten shots to do this entire shoot on. I let everybody know and we just kinda laughed it off and said ‘oh well guess we better make 'em count, right?’ The shoot was broken up into four different scenes, each one with a unique location and outfit change so I really only need four perfect shots out of the 10. We start shooting and I’m positioning the models, running back to look through my camera, rearranging the set, repositioning the models and then running back to check how it looks through the view finder again and again, and then once it feels just right I’ll release the shutter. We repeat this process for all four scenes. I drive back into Austin and drop off the film at this one hour photo lab and I’m sweating. The guy finally emails me my 10 photo files and somehow, somehow, each one is perfect. No closed eyes, no light leaks, everything’s exposed correctly and every hair was in place. I couldn’t believe it. Everyone really buckled down and pulled a lot of weight. Good shoot and good people.

JG: Where can people see more of your work?

SP: The easiest option is my instagram - @stvnlance or for more variety, quality and to see all of my stuff you can check out my website - https://www.stvnlance.com/

“Tanner Webster - crew leader on static peak, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming 2024.

Crew Leader. Friend. Finder Of Things. Mentor. Waller and Baller.

When Tanner comes to mind I really can’t help but grin. This dudes got this crazy charismatic positive demeanor about him. I think that’s part of what makes him such a good crew leader is you just wanna rally behind that smile.”

Photo by Steven Phipps

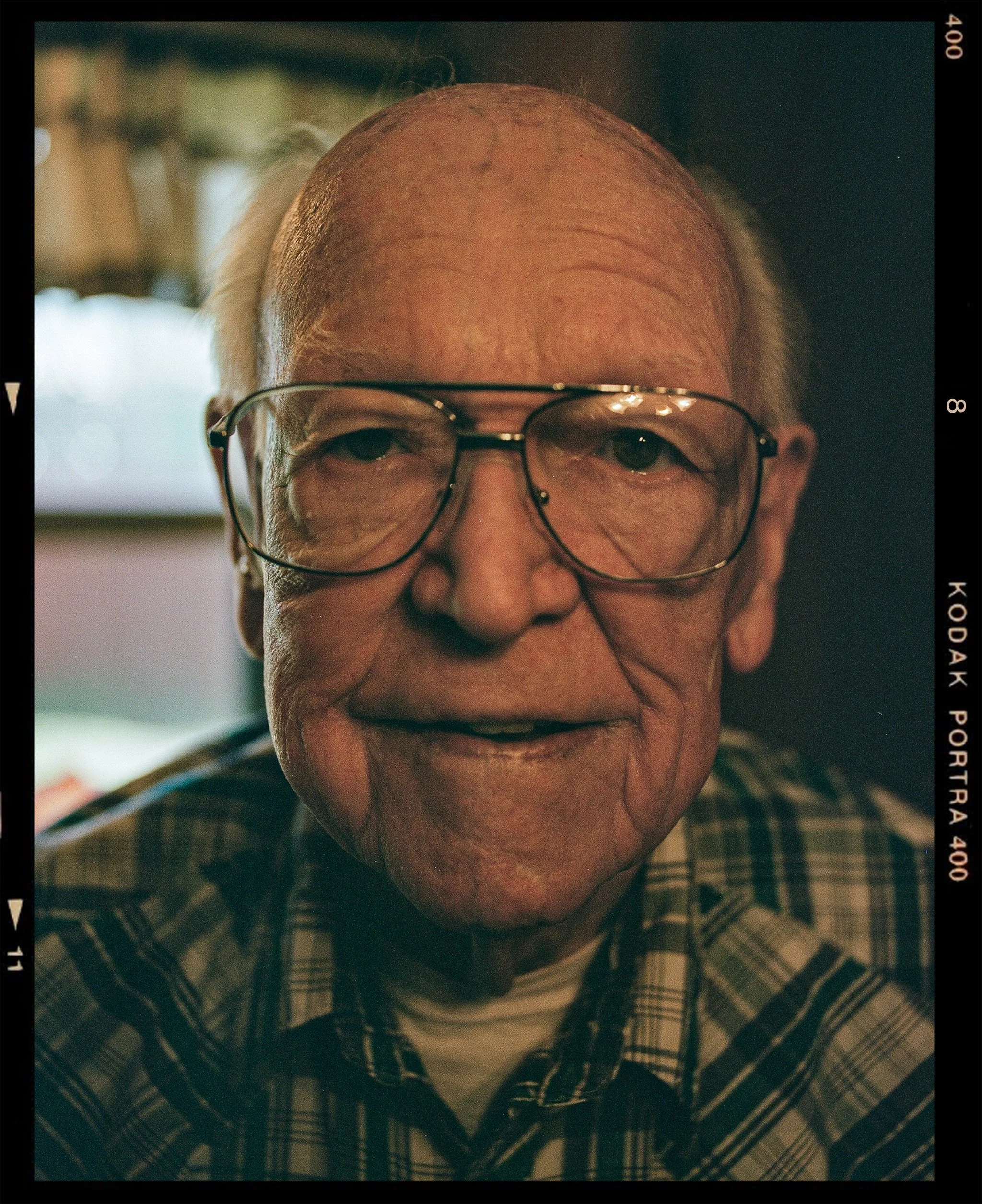

“This is Sonny Boyd — one of the Dallas detectives who escorted Lee Harvey Oswald into custody after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. He was from the same small town as me, and I grew up picking blackberries off his fence when I was supposed to be at baseball practice.

In April 2024, I went over to his house to take these portraits and listen to some of his stories. My mom, who was friends with him, came along. It was a really nice day.

Sonny passed away about two weeks later, so I think these might be the last photos ever taken of him.”

Photo by Steven Phipps